Jericho by Alex Wylie

Funnily enough there's only airbetween us, no wallof monumental moment and renownto storm at, blow up or bulldoze down,nor lock to twist off with the minor key of song;

though for some reason – as you mark well –I've brought alongmy own wall-flattering trumpet to blowwith one desire, to enter Jericho.

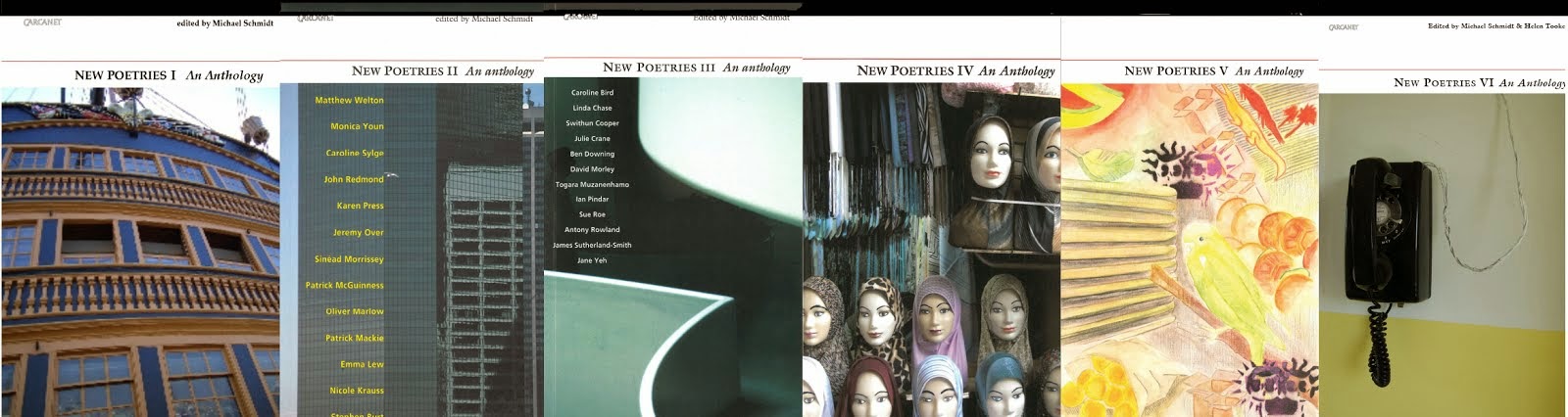

from New Poetries V © Alex Wylie

I didn't notice for weeks. Perhaps my own upbringing, permeated by Bible stories, left me over-familiar, too complacent for close reading: the story of the Israelites marching around the walls of the besieged city of Jericho every day for a week until the sound of their trumpets (and Jehovah’s wrath) brought the walls to the ground. Or perhaps it was that off-hand opening: 'Funnily enough...' The letters are even deceptively simple in shape. For whatever reason, I had been reading the second-to-last line, as one might expect it, as a wall-flattening trumpet. But wall-flattering? What to make of that?

So, let’s go round it again. The poem is addressed to someone, thus there's some kind of relationship in play – but the speaker is disconcerted by the fact is that 'there's only air / between us, no wall'. It feels like there should be a barrier between them; the feeling is so strong that it is itself a barrier. In the tradition genre of carpe diem poems – exemplified, in English, by Marvell's 'To his Coy Mistress' – the poet employs his eloquence to persuade an unwilling woman into accepting his advances. The story of Jericho might seem like a perfect conceit to deploy in this situation. But the declared permeability disarms the usual demolition strategies; and the superbly Augustan metaphor (not forcing a new trope, but finding it in the language itself) of the 'lock to twist off with the minor key of song' implies, through the metonymic connection of song and poetry, that poetry isn't going to guarantee access, either.

But the speaker – the poem's Joshua – has brought along his 'wall-flattering trumpet', one that will not bring down but actually build up the wall, however insincerely. In fact it already has: the wall 'of monumental moment and renown', with its play of sounds, has been raised by the poem’s diction to a rather grandiose stature. Distracted by the wordplay in the penultimate line, one might not notice the in-built idiom, to blow one's own trumpet. So the trumpet – a variation on the poet's lyre or lute – is to flatter the wall, but also the poet himself. His stated desire, 'to enter Jericho', seems more and more like a pretext for this self-aggrandisement.

But this is what happens in the classic carpe diem poems: the poet cannot just assume the girl's objection or the other obstacles; describing these provides opportunities for the poet to display his virtuosity, just as much as he uses it to overcome them. 'Jericho' extends the carpe diem tradition by commenting on it, sending up the masculine hubris of the genre. Most telling is the aside '– as you mark well –' in which the poet acknowledges that his listener is not naïve; she's heard this one before, and if she's going to accept the poet it won't be because she's left defenceless by his rhetorical prowess. But if this poem isn't intended to do exactly that, still, it finally got through to me.

No comments:

Post a Comment